Show & Tell Performance Practice

at Bastion Point Beach on Wednesdays & Fridays March 3, 5, 10, 12, 16, and 19 at 11:30 am

weather dependent

For the last month and a half I have been researching dance documentation. In particular, I am looking at the ways in which documentation can feed into creative practice as well as communicate about a dance experience.

I’d like to share what I’ve been up to, so over the next three weeks I am advertising my dance performance practices. As I don’t have a dance studio, dancing/practicing outside and in public is something I am often doing, but I for these occasions I have chosen Bastion Point because it is such a central hub for our community.

I will be working . Padma Newsome will also join me with music. We will be working with materials generated from an early incarnation of “No Dancing, No Singing, No Mingling,” which you can see in a video document of a livestream performance below. Please join us!

Drop-in for a few minutes before your walk, swim, or surf or come for the whole thing.

this project is supported by a grant from:

This is a COVID-safe Event! (I am required to put this up on my website)

Please do a symptom self-assessment prior to leaving home and don’t attend if you are unwell or have been instructed to isolate or quarantine.

We will maintain at least 1.5m physical distance between each other at all times.

To minimise movement, we will not mingle.

We will observe current requirements for face covering, and observe cough etiquette and personal hygiene measures.

Click the button below to see my COVID-safe checklist:

livestream performance from November 29, 2020

“No Dancing, No Singing, No Mingling”

Despite this striking imperative from NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian earlier this year in the context of social distancing, we take the tonic of collaboration, experimentation, music, dance, and technologies of connection. Here amongst restriction and devastation we explore fluidity and buoyancy through play with ornamentation, following interest or fun:

Turn, divide, alternate, undulate, shake

Graces and ghosts

Lean, slur, and fall up or down

Approached by leap

Resolved by step

Fluidity creates buoyancy

We take a wide girth on a narrow path

When immersed

Fluid exerts force

On any body

Buoyancy always points up

Pressure increasing with depth

music: Padma Newsome

dance: Susannah Keebler

camera: Larry Gray

The performance "No Dancing, No Singing, No Mingling” is presented as a part of Melaka Art and Performance Festival 2020

MAP Fest 2020, proudly supported by:

E-Plus Global

Tony Yap Company

ImPermanence Productions

Excerpts of some of the written research:

Show & Tell: Dance and Its Documents

In the Context of Crisis, a creative research of dance documentation methods in post-disaster Mallacoota.

Show & Tell explores how data and experience live in a body and can be shared in dance performance, transforming cultural data into art that bridges individual experiences and fosters mutuality, artist-community partnerships relationships, and community resilience.

This work comes out of being extremely dissatisfied with some of my past documentations and the way they were dis-integrated from the pieces they were documenting. In my initial research, I was inspired by Marc Kociejew’s article, ‘A Material-documentary Literacy,” which asserts that the materialisation of information brings greater understanding of both the subject, document, and documentation processes. This connects directly to my creative interest in the performer-artist-audience relationship.

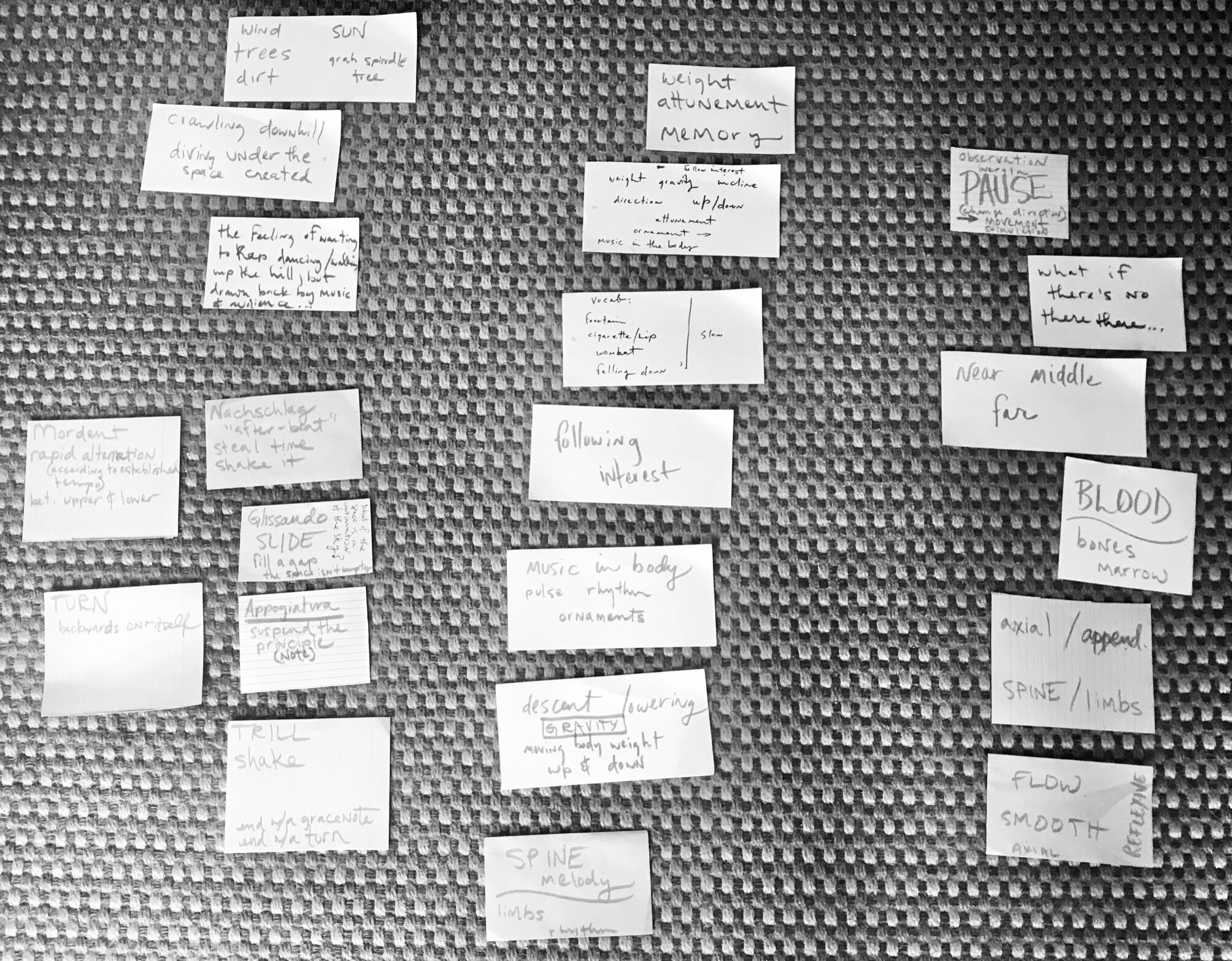

I decided to focus on a piece that I performed in a livestream (shown above as part of the advertisement), which was part of a digital version of Melaka Art and Performance Festival 2020. (I previously performed at MAP Fest in Melaka in 2018.) It was an improvisation with fixed vocabulary that I developed in collaboration with Padma Newsome. Its title, “No Dancing, No Singing, No Mingling,” is take from a striking imperative from NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian earlier in 2020 amidst the context of social distancing. Padma and I wanted to use it as a title in contrast to our explorations. Originally the title of the music was “Ornaments Only,” and came out of an improvisation that Padma did where he was working on a particular technique.

Here, Padma and I perform a very open score version of the last segment of “No Dancing, No Singing, No Mingling”

During this process, my attention was drawn to the movement from improvised material to “set” material and the process of deciding what I should do with the choreography. As I sought to gain more material literacy of my own making and documentary processes, I realised that my practice of “setting” dance choreography (as opposed to improvising) is one of documentation. I knew previously that dance for me was a way toward understanding my experiences, but I had not understood how. This gives me some clarity and food for thought in considering or deciding when and where I might be shifting and sliding my choreography on the open score (more improvised) and closed score (less improvised/more set) continuum.

Kociejew writes about the “significance of documentary practices helping information stabilize and emerge.” He writes that a document must be created. An informational object, like an artwork, and is not necessarily a document on its own, it must be processed. Conversely, a document alone does not transmit information, it needs practices to materialise the data. (Kociejew, p.103)

Iconic photographic documentation of American Document from “Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs” by Barbara Morgan

This brings to mind Martha Graham’s statement in the Barbara Morgan book, “Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs,” a 1941 collection of Morgan’s iconic photos depicting Graham’s early works. Graham states:“Dance is an absolute. It is not knowledge about something, but is knowledge itself.” In this book Morgan speaks of the loss of a life’s work, “the dancer’s fugitive art.” (Morgan, p) This was famously echoed by Peggy Phelan in “Unmarked: The Politics of Performance”:

“Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance. To the degree that performance attempts to enter the economy of reproduction it betrays and lessens the promise of its own ontology. Performance’s being ... becomes itself through disappearance.” (Phelan, p 146)

While I am enamoured with dance’s resistance to commodification, I argue that dance importantly lives on in other art forms, but additionally it is passed on from one dancer to another and from dancer to audience and into the lives of audience members.

My body is marked by the many dances I have as well as by many of my life experiences. In the period following the New Year’s Eve bushfires I experienced in my home, Mallacoota, I felt a paradoxical detachment from my material possessions and at the same time, I felt overwhelmingly grateful to have not lost my home and its contents particularly my dance/performance books which are commonly expensive to replace because they are small press printings or are out of print. I reference and use them often in practice.

Sandra Parker’s article, “ The Dancer as Documentor: An Emergent dancer-led approach to choreographic documentation,’ strikes a chord with my current exploration. In particular, her endeavour to align documentation practices with the creative processes “where the bodies no longer mute in side the frame.” As a practitioner who is often working as both the performer and choreographer simultaneously, I face the problem of engaging the skills of self-documentation, reflection, and performance at one time.

In the process of wrangling with this conundrum, I remembered a piece by Bill T. Jones which I have only ever seen on YouTube, called “Floating the Tongue.” This piece demonstrates a virtuosity of a dancer as documentor and data transmitter.

It has become a touchstone and muse for me in this project. With documentation as a primary subject matter, I have felt free to consult works that I have never experienced live. Whereas, in the past, I have always felt it is important for me to use references that I have first hand knowledge of and experience with.

Originally made and performed in 1976, I have seen two different video documentations of “Floating the Tongue.” The first is a 1999 performance by Jones himself and the second is performed by Leah Cox in 2010. Jones has said that he made the piece in order to show that the dancer is a thinking artist. In this he succeeds, demonstrating a virtuosic practice of articulating and linking, thought, language, and dance on the spot infant of audiences.

The two performances and dancers are radically different, however, the form remains the same. First the performer arrives and supposedly develops the “phrase.” Second, he/she performs the phrase. Third, the performer performs th phrase and simultaneously articulates the phrase with words as if he were teaching the phrase. Fourth, he/she performs the phrase and at the same time speaks whatever he/she is thinking or feeling “without censorship.” Fifth, he/she allows what is said to affect what is being done.

A rainy- or hot-day indoor practice in my tiny lounge room. Here, I am remembering the piece and vocalising aspects of the materials in a pseudo-Bill T. Jones way.

Here, experiemnting with simultaneous narration. (Padma on camera.)

Around the time I was studying “Floating the Tongue,” by mimicking this structure, I came across, “Document Phenomenolgy: a framework for holistic analysis” by Tim Gorichanaz, which looks at the subject of how an object becomes a document. The framework seemed easily applicable to a “set” piece of choreography or to a video recording/documentation of an improvised dance. However, I wanted to explore whether it could be applied to a live improvised piece.

I set out to make this the focus of my live performance practices which I did across three weeks at Bastion Point. Some aspects of woking with the framework didn’t really work in that setting for several different reasons described here below.

Here, my colleague, Chelsea, has recorded three layers (abtrinsic, adtrinsic, and intrinsic properties) of the framework while watching the recording of the livestream. We did this together on a Zoom call. I then layered the recordings together with the video excerpt.

Here, I recorded three layers (abtrinsic, adtrinsic, and intrinsic properties) of the framework while watching the recording of the livestream. We did this together on a Zoom call. I then layered the recordings together with the video excerpt.

Here are all the layers played at once.

Here, I try to explicate different “docemes” or aspects of documental information (Gorichnaz, p.1124)

During the six public sessions at Bastion Point, Padma and I practiced in different ways and this was on view for anyone passing by. Sometimes people would stop and watch impromptu of these very few got involved or participated in discussions. Sometimes people came because they knew we would be there from my advertisement. Most of these were eager to watch, happy to listen to me share what I was working on, and participate in a discussion, However, there seems to be a reticence to engage directly with the materials and the reflective and documentation materials.

I gather this, because few of them took it up when offered as an activity. I feel a more controlled environment, like a studio or theatre, would be more conducive to this activity where I, as the choreographer, can more easily visibly and physically frame the documentary activity with props that won’t blow away and give invitation without impeding on audience agency.

On this page I have shared some of the conversations, explorations, and experiments undertaken during Show & Tell in a roughly cut together audio-visual format. Working towards discovering integrated processes of documentation is important for my work as both a researcher and as an artist. As discussed above, for an artist, documentation processes offer new pathways towards understanding one’s practice, but they also potentially offer new pathways for audiences to enter dance works with more depth.

It is apparent that the phenomenological framework for documental becoming can be applied to improvised dance. However, this is difficult to self-administer, so it is more useful at least for me at this point to continue to seek out ways of involving others, both artists and audience members who are not doing the performance to perform integrated documentation processes.

From the course of the project, I still have an abundance of data in the form of video, audio, writing, artifacts, and a small amount of drawing that still needs processing. This suggests to me that extra time be given to the processing of materials as I move forward. I will continue experimenting and researching moving between both indoor and outdoor performance practice environments and experimenting with the practice-performance continuum.

A recorded (longish) conversation about the framework between me, Padma, and cthy Pirrie who comes in half-way through. I layered the audio over some video on the same day. The first video is before the coversation. The second is after.

WORKS CITED / WORKS READ

Auslander, Philip. Liveness : Performance in a Mediatized Culture. Routledge, 1999.

Bank, Motion, and Motion Bank. “Using the Sky - Motion Bank.” http://scores.motionbank.org/dh/#/set/introduction-to-concepts.

Foster, Susan Leigh. Reading Dancing: Bodies and Subjects in Contemporary American Dance. First edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Gorichanaz, Tim. “Conceptualizing Self-Documentation.” Tim Gorichanaz, January 1, 2017. http://timgorichanaz.com/writings/Academic/concepselfdoc/.

———. “Self-Portrait, Selfie, Self: Notes on Identity and Documentation in the Digital Age.” Information 10, no. 10 (September 26, 2019): 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10100297.

———. “Understanding Self-Documentation.” Drexel, 2018.

Kosciejew, Marc. “A Documentary-Material Approach for Performance.” Proceedings from the Document Academy 5, no. 1 (July 2, 2018). https://doi.org/10.35492/docam/5/1/3.

———. “A Material-Documentary Literacy: Documents, Practices, and the Materialization of Information.” The Minnesota Review 2017, no. 88 (2017): 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1215/00265667-3787426.

Kozel, Susan. “Process Phenomenologies,” 54–74, Routledge, 2015.

Lehmann, Sophie-Ann. “Cube of Wood:Material Literacy for Art History.” Lecture, Inaugural Lecture presented at University of Groningen, Nederlands, April 12, 2016. https://www.museumderdinge.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/cube_of_wood._material_literacy_for_art.pdf.

Morgan, Barabara. Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs. Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1941.

Parker, Sandra. “The Dancer as Documenter: An Emergent Dancer-Led Approach to Choreographic Documentation.” Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices 11 (July 1, 2019): 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1386/jdsp.11.1.67_1.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. 1st edition. London ; New York: Routledge, 1993.

Reason, Matthew. Documentation, Disappearance and the Representation of Live Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230598560.

Walton, Jude. “By Hand and Eye: Dance in the Space of the Artist’s Book.” School of Communication and the Arts, Faculty of Arts, Education, and Human Development, Victoria University, 2010.